Caridad de Baldor

In September 2006, a formerly young Havana gent - formerly young, formerly from Havana - published a post about his school, a place which had much meaning in his life, then and now - Colegio Academia Baldor. One of the things written therein expressed not just nostalgia, but much regret...

"My buddies and I started at something equivalent to a Kindergarten level - 'Pre-Primario B,' as defined by the school administration, but more challenging than Kindergarten. Call it preparation for First grade, if you like. The classes were subdivided into groups, A, B, C, D, and so on, depending on how many 'lil students were registered. Our teacher - whom we loved - my friend Carlos B admitting recently he 'had a big crush on her' was Mrs. Caridad Lobato. Many years ago she popped into mom and dad's pharmacy, in Miami, and left a phone number, asking that yours truly contact her...did I do so? Of course, being an obnoxious teenager or too-busy young man then, the answer is - NO. To my shame! And then the phone number was lost...and now, of course, 'we,' meaning the four of us who have reconnected from Pre-Primario B and who were fortunate to have her as our teacher and mentor are desperately looking for her.

Moral of the story: When your beloved teacher comes calling, call your teacher!

And if anyone who reads this can help with this quest, we will be forever grateful."

Well! There is much joy in being able to report that we now are indeed forever grateful! For our much-loved Caridad Lobato Meunier has been found, and she was literally under our noses! And for this we are forever grateful to Joaquin P. Pujol, former Baldor Academy student, whose comment to the post on Baldor of September 2006 reads thus:

"You mention a former teacher of you at Baldor. She now lives in Miami and her address is

Caridad Lobato Meunier

(Address and phone not shown for privacy reasons)

I tought you may want to get in touch with her

Joaquin P. Pujol"

Did we ever want to get in touch with her, Mr. Pujol! If you read this, Profesora Lobato's "kids" profusely and with gratitude thank you for letting us know her whereabouts.

When the blogger emailed his Band of Baldor Brothers with the news, a joy-filled response from Carlos Bidot, who confessed to having "a big crush on her" back then, included a caveat, which went something like this: "Everybody hold off contacting her...I must be the first to do so!" And of course we honored brother Bidot's wishes. He both dutifully and duly contacted our teacher, and then reported back to his friend Quiroga: "She is very happy to hear from us - I'm gonna get us all together at my place. You must call her, as she remembers you well."

"She remembers you well..." I was honored! Must have done something right in her class and not been much of an annoyance, as most 5-6 year-olds can be. Sometimes annoying ways can be the hallmark of the 55+ set as well. This time, the former student did not fail in his duty and he called his beloved teacher; after a very pleasant conversation during which the meeting date and venue were confirmed, the student could not help but be impressed by his teacher's power of recollection and clear-as-a-bell mind.Maybe she remembers the writer well because he was probably the shortest one in her class and she had to gingerly watch her step lest she accidentally step on him...

And so, after much anticipation and preparation, the students and their teacher experienced a wonderful reunion, indeed a love fest, on Saturday the 7th of February...over five decades after we had experienced the warmth, comfort, and love of Caridad Lobato Meunier's teaching in her "Preprimario B" class.

This is how she remembered us then - one only wishes the image was as clear and bright as her mind still is...

Baldor Academy Yearbook - 1955-1956 school year

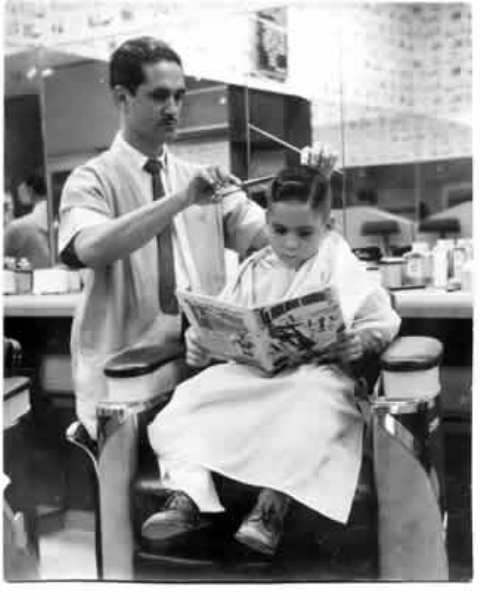

Baldor Academy Yearbook - 1955-1956 school year ...as he waited to get a ride to school in September 1955, aboard his dad's nifty '55 Chevy BelAir, accompanied by his aunt Dolores Granja, another much-loved woman in his life - another mother, really. Truly and painfully missed, aunt "Loli," as the little boy and his sister used to call her, is and will be until the day of our joyful Reunion; only God knows the day. His dad, no doubt seeing the "Kodak Moment" of his little boy off to his first day of school in Baldor, took his Kodak and recorded aforesaid moment in front of the apartment building where we then lived - Number 1303, Calle 42 - yes, 42nd Street, but not New York's - Miramar neighborhood, Havana.

...as he waited to get a ride to school in September 1955, aboard his dad's nifty '55 Chevy BelAir, accompanied by his aunt Dolores Granja, another much-loved woman in his life - another mother, really. Truly and painfully missed, aunt "Loli," as the little boy and his sister used to call her, is and will be until the day of our joyful Reunion; only God knows the day. His dad, no doubt seeing the "Kodak Moment" of his little boy off to his first day of school in Baldor, took his Kodak and recorded aforesaid moment in front of the apartment building where we then lived - Number 1303, Calle 42 - yes, 42nd Street, but not New York's - Miramar neighborhood, Havana.No doubt she remembers her smart boys thusly - am speaking of my Baldor brother-friends Carlos Bidot and Carlos Cueto, proudly standing in the yearbook graphic with their medals earned for academic excellence - they were the "math whizzes," envied by their friend "Quiroguita" for that skill, in which he was lacking.

True, this was First Grade, a year after we were blessed to be in Caridad's class, but physical appearances were very much the same; she laid the groundwork for the pair's academic achievement - indeed, for all her "Pre-primario" boys' progress, including the writer's.

And this is how we remembered her, as she appeared in the 1956-1957 school yearbook...by then, we were first graders at Baldor.

Looking at that page in the yearbook, the blogger was reminded of another fellow blogger and indeed, Baldor Brother - for as far as this writer is concerned, all of us who shared the Baldor experience whether from the Class of '32 or the Class of '61 can be said to be one huge family of Baldor-eans, brothers and sisters all. The writer is speaking of Patricio Texidor, who with his twin brother Roberto is featured on the page, graced by Dra. Lobato. If you pay attention, you'll note Patricio's blog is linked to this one. A good one it is - you should take a look at Texidor Blog.

Havana Blogger had the good fortune to meet fellow Baldor Brother Patricio at Cuba Nostalgia in Miami, back in May, 2006...

Another Baldor student done good! Grammatically correct that statement may not be, but it is just a way to convey the feeling - the writer cannot help but think Caridad Lobato Meunier had something to do with that success. One wonders if Patricio remembers her as well as we do; perhaps the page from the yearbook helps recover treasured memories.

And in our group, in that year before first grade when we met our wonderful teacher, also were present Warren and Willie, who 53-54 years later once again reconnected with their classroom mother - "classroom mother?" - you wonder if that is not carrying it too far but...no...because that is who our teachers at that tender age stand for - our parents; our mothers and fathers away from home - in loco parentis.

This is how Caridad would have recognized them, were we able to miraculously reverse the Hands of Time and go back to 1955-1956...

Warren appears in the bottom image, first row, first on the left - your left, reader. The Holy Mass and Communion were held at San Juan de Letran church, 11th of May 1957. In poring over the pages in the yearbook, Baldor blogger, who himself did not make his first Communion that year - it would not be until May 1958 - noticed friend Wilfredo - "Willie," as we affectionately know him now - was absent from the lineups. Nevertheless, we did not want to leave Willie out of the picture, so here he is, as Caridad Lobato recalled him...in the days when, like the writer, he had copious hair.

The image is not very clear; apologies to the readership - it is a "photo of a photo," done in the best ad hoc state of the art technique; he was not taking Communion at the time but was present at a family baptism. And, wouldn't you know it? Of our group he is the true poet, as you shall see and indeed hear before you finish reading this post.

The image is not very clear; apologies to the readership - it is a "photo of a photo," done in the best ad hoc state of the art technique; he was not taking Communion at the time but was present at a family baptism. And, wouldn't you know it? Of our group he is the true poet, as you shall see and indeed hear before you finish reading this post.Throughout the afternoon, we engaged in pleasant conversation and exchanged reminiscences of our student and city life with our teacher, who also became acquainted with the spouses and children of her "kids."

And one could tell she much enjoyed reminiscing and re-telling, bringing back her memories of a long-ago time which yet seemed just like yesterday, as is clear from her focused conversation with her former pupil Carlos Cueto. We asked her many questions, and she kindly opened her Memory Vault, sharing anecdotes and facts from those days with us.

"So, Profesora - where did you live in Havana?" "It was on 25th Avenue, between N and O Streets." That was the first of many queries - so we'll summarize the rest and let her tell her story.

"I liked working at Baldor; the students were well-disciplined, the teachers well-treated, respected, and appreciated by the school administration. Good teachers received public recognition from the school administration. My salary was $115 monthly in the mid-fifties, and that was considered good pay at the time. My teaching career began in the late '40s - 1947 in fact; I was working in the town of Bauta. Later I was hired by Baldor, and taught there until 1961, when the school was taken over by the revolutionary government and closed. Fortunately, I was not there the day they swept down on the school and, therefore, did not witness the sad end of Baldor Academy.

The Baldors were good to me; in fact, Aurelio Baldor was one of the witnesses at my wedding to Carlos Meunier in 1950. I knew the Baldor family; Aurelio's brother Daniel was principal or director of Belen School in Havana; then there was Carmen Baldor, and Jesus, who ran the Baldor girls' boarding school."

Well, as it turns out, this bloggin' Baldor boy got to know a few Baldors himself...not bragging, just glad to have made their acquaintance. One was - IS - my cousin; by marriage that is, to a blood cousin - Azucena is her name, daughter of Jesus Baldor, but our family and her friends call her "Susi."

Can you find a Fifth Grader we will call "Singing Susi" in this page of the yearbook? If you find the Lily, you find Azucena. One hopes Susi will not mind this flowery play on words and names - assuming she reads this, that is...

Now, back to Caridad. "After some false starts, my husband and I finally left Cuba December 5, 1966. First, we went to Spain and spent five months there - I worked in a factory making women's purses in Madrid. When we left Spain, we traveled to Portland, Oregon and stayed with my sister and her children until eventually we made our way to Miami."

We asked her to tell us a little bit about her husband. "We were very close, perhaps because we never had children, unlike my sister who had six. He was born in Belgium. As a young man, he traveled to Cuba, liked what he saw, and decided to stay. He was a musician and founded a cuartet, 'Los Bucaneros;' they made TV appearances, in variety shows such as Casino De La Alegria and Jueves De Partagas.

This was in the late '50s. Unfortunately, 'Los Bucaneros' did not last very long - castro came and...well, we know what happened; it was all over by 1961."

The DVD case title image is from Cubacollectibles.com - this is not an ad for Cubacollectibles; however, should curiosity get the better of you, order the video and watch the 1954 debut of Jueves De Partagas. Unfortunately, 'Los Bucaneros' are not featured; this was before their time. Since we are speaking about schools, teachers, and learning new facts here, time for a quiz: Who is the actress holding the Jueves De Partagas sign?

"After we arrived in the United States, eventually my husband went to work at Les Violins Supper Club in Miami, on Biscayne Boulevard. He was one of the 'Singing Waiters.'" If anyone reading remembers spending a nice evening at Les Violins from the '60s through the '80s, you may have seen Mr. Meunier perform. The writer was fortunate to enjoy several such evenings at Les Violins, but regretfully neither idea nor recollection which of the Singing Waiters was Mrs. Lobato's Other Half. No doubt the oblivious young blogger enjoyed his performances. This was a fun place; unfortunately the club closed down about 15 years ago.

Cover-souvenir photo holder - Les Violins Supper Club, 1966 - courtesy Nick and Teresa Quiroga

"And what did you do after settling in Florida, querida profesora,?" the "kids" asked. And she graciously shared that experience with her attentive audience.

"I taught public school in Miami for twenty years, from 1972 to 1992 and retired from the Dade County Public School system. I spent fourteen years in Miami Shores Elementary and then my last six teaching in Sweetwater Elementary." "Sweet!," thinks her former Baldor student-cum-blogger; she returned to the profession so clearly loved.

Perhaps one or more of her former students from these schools who remember her as fondly as we do will read this and "drop in" to send a warm greeting to his or her teacher Caridad.

From little readers, for little readers; thanks to our dear classmate Willie Hernandez, you get a small glimpse into our classroom day, when in Baldor, and throughout Cuba, First Graders would read and recite from this small book. "El Nuevo Lector Cubano," reads the title - "The New Cuban Reader;" indeed created for new and upcoming little Cuban lectores in those Fifties days. The lectores now in their fifties, together with their teacher, wistfully remembered those nostalgic times when they took their first tentative steps into the world of the printed word.

What memories were elicited, one wonders, as she paged through the little treasure Willie had conjured up for this occassion? No doubt happy ones, as evidenced by the frequent, easy and radiant smiles constantly written on her face as the evening wore on.

One memory she shared with us, about our first steps taken to acquire essential reading skills. "You may not remember," she said, "but we also used a reading book titled Elena y Danny." Elena y Danny, blogger tried recalling - then it hit him! "Profesora," asked her former student, "was there not a dog in the stories, their dog, named Sultàn?" "I believe so," she nodded. Then from the vault of blogger's memory, a memorable sentence, a command to Sultàn really, which somehow he still recalls, welled up: "Salta, Sultàn, salta!" "Jump Sultan, jump!" Or as this would have been expressed in the popular Dick and Jane reading series in the USA - "Jump, Spot, jump!"

And as the evening inevitably and irresistibly moved on, we spoke nostalgically about our beloved school, the source of our common, undissolvable bonds, our raison d'etre - the reason for our being together this unforgettable day. Then our friend, brother, and classmate - interchangeable terms, all - brought out some images, captured fragments of light enlightening us and helping in the reminiscence, recollecting, remembering, with the joy and the pain inherent in those acts of remembrance. "Recordar es vivir." "To remember is to live again;" to live the joy and also the pain of our childhood.

By April 2001, when these photographs were taken by Carlos, the name "Baldor" was no more, at least when it came to the physical location of Academia Baldor. The school had been re-named by the "revolutionary educators" after some minor entity in the pseudo-pantheon of the castro-cult. Somehow, the rusting bars give the place the appearance of a prison...a prison of the mind, no doubt. The middle image would be familiar to Baldor students - the main building with the marble stairs; the building where many of us in the elementary grades had our classrooms and where we dutifully assembled in the mornings for our orderly entrances into class.

The bust of Jose Marti still stands across from the same steps; somehow Carlos created an eerie, ghostly image of Marti...the ghost of Cuba's greatest patriot may perhaps wander the grounds and wonder how evil men could misappropriate his thoughts, his ideas, and pervert them in the pursuit of tyrannical control and for poisoning the minds of innocent children as well. "A school is an anvil for souls," reads the inscription beneath the bust. Except that, school in Cuba has become an anvil for hammering free souls into the oppressive mold crafted by the madman headmaster; the ideals and ideas of teachers like Caridad Lobato betrayed by a man - if he can be called that - who himself was blessed by a good, and religious, education in Belen School, under the Jesuits; alas, he did not learn from Jesus, but from satan...

Carlos' camera recorded yet more Marti aphorisms recorded on the walls of our school; these were already up when our little band was brought together in 1955; much meaning in few words, words regretfully unheeded by those who should have taken them to heart. One is not speaking of the girls and boys, men and women, of Baldor here - the writer's experience is that the vast majority of Baldor-eans he has known indeed have walked the talk expressed in these few words.

Let the former Pre-Primario B student translate, albeit poorly, from top to bottom. Perhaps if Caridad reads this, she will graciously grade her student - as she once did; he will accept said grading gracefully and gratefully.

"Children are the hope of the world"

Perhaps this should now be engraved on the same walls, as a warning to those who have turned these great thoughts upside down in the pursuit of power for power's sake...

"If anyone causes one of these little ones who believe in me to sin, it would be better for him if a large millstone were hung around his neck and he were thrown into the sea." This, as Jesus Himself so succintly put it, is recorded in Mark 9:42 - for those who wish to be reminded; you will not read this in the turgid pages of Das Kapital, Mein Kampf, Granma, or other such delusional drivel which is crammed down the throats of helpless, regime-compliant students in Cuba's mind-prisons masquerading as schools, in other unfortunate places, in other times too.

Perhaps none of us will live to see this - certainly, as Caridad herself said, "I do not expect to live long enough to see Cuba again" - but we hope and pray someday a new generation of Cuban children will attend a newly-risen - from the ashes of the revolutionary "educational" trash-heap - Baldor Academy, as we remember it to this day...

"At least," as our profesora had previously mentioned, "I was blessed in that, when Baldor was taken over or intervened, which was the term then used by the authorities, in April 1961, I was not there to witness that tragic event." Blessed too was the blogger and former student, by then having been exiled with his parents and sister, for almost six months, at that time attending Riverside Elementary School in Miami, Florida - where he felt much like a fish out of water, yet still harboring hope he would once again re-unite with his beloved buddies from Baldor; unbeknownst to him, said reunification would not take place for over 40 years! But take place it did - and he sees it, and will regard it for eternity, as another personal victory against fidel and his minions. It is our victory, brothers, sisters, profesores y profesoras de Baldor - to have escaped the claws of the beast, now prostrate and impotent as his miserable life ebbs away.

Time kept flying by as the conversation and good cheer both flowed, as if we had seen each other just yesterday, in class. We were hungry and thirsty, not only for beautiful and bountiful memories, conversation and camaraderie, but also for food and drink. "Man does not live by bread alone," but let us remember that companion and companionship come from the Latin cum panis - "with bread," referring to those we break bread with, in fellowship and with affection. So the Baldor companions made sure la profesora did not go hungry or thirsty.

Mrs. Bidot, ever the gracious hostess, made sure our teacher did not go thirsty, pouring her a refreshing, classic drink, as friend Cueto watched, possibly thinking of adding some fine Bacardi rum to his Coke. The blogger-photographer certainly thought this would be a fine thirst-quencher to pour for himself, but he had other assigned duties to fulfill.

La profesora was getting hungry, and so were the rest of the attendees; not to worry - good old American Entrepeneurship, taken to heart by Caridad's students, to the rescue!

Our quasi-official photographer Carlos Cueto's camera captured the debut of the Baldor Brothers' Barbecue Stand! Franchises available? Sorry, no...this is a labor of love, and too many cooks spoil the kitchen. Master Chef and host Carlos Bidot, more or less assisted by his apprentice Igor, oops - Freudian Slip - Albert - ensured no one starved, especially Caridad, who had already been exposed to a restricted diet courtesy fidel's hell-kitchen for several years.

Emerils or Bobby Flays we may not be, but no one beefed about the vittles!

The reminiscing and anecdote-telling continued; time seemed to have stood still, after all...we felt as if we were back in Pre-Primario B in 1955. Profesora Lobato was enjoying her "kids" once again.

Willie posed with our teacher, his shirt pridefully pinned with one of the medals Baldor would award students for excelling in different fields of scholastic endeavor, and for demonstrating good character and study habits as well.

This is the medal Willie wore, a beautiful gift which each of us in our Beloved Band received from our absent classmate Nelson, a bit more than a year ago. This award Baldor students would have received for "Aplicación," literally "Application," but more accurately translated as "Scholarship."

Some of the "brainiacs" in the group - not counting the Baldor blogger-boy - who sometimes unconsciously whistles the Scarecrow's song from The Wizard of Oz - "If I Only Had a Brain!," found ourselves suitably decorated by the end of the school year, when awards and medals were handed during special ceremonies. A young man could be weighed down by all that medal metal, but this did not seem to faze our class brother Bidot when he proudly posed with his in 1956.

You wonder where all this decoration, achievement, and medal talk is leading to...remember earlier it was said we were reminiscing and telling anecdotes, laughing about amusing classroom moments and such. Well, the subject of Willie's Scholarship medal gives us the opportunity to relate one of these amusing, indeed funny, stories. Willie won't mind; he is kind and possessed with a good sense of humor - which you need when you hang around us!

Here is Willie's Baldor report card - we informally referred to them as "boletines" - which recorded his academic achievements in Caridad Lobato's Pre-Primario B class. No, dear reader - you do not need glasses; the image is blurry - again, chalk it up to less than optimal, improvised "field photography conditions" - no scanner available at the time. Give the blogger-photographer a barely-passing grade here, if you wish. Perhaps it will be possible to provide a better graphic later.

This is the front of the "boletin." At the time - 1955-1956 - Willie's family lived on San Francisco Street, No. 464-462. This is for those of you readers who might be familiar with Havana. Maybe this was your neighborhood too?

The grading system should be explained a bit, so things will make some sense. The grading scale was numerical. The system is explained in the boxes at the bottom of the document. The leftmost square box provides the number scale for "Disciplina" - class behavior; 1 meant "Terrible;" 2 was "Bad;" 3 was "So-so;" 4 was "Good;" 5 was "Excelent." The box labeled "Aplicacion" - scholarship - explains the grading system for academic subjects; no grading "on a curve" either; if you scored less than 60, you flunked the subject. Period. No whining! If you scored 90 to 100, on the other hand, you were classified as "Sobresaliente," or "Outstanding." If you were a Sobresaliente student in Baldor, give yourself a well-deserved pat on the back.

This sets the stage for the amusing part of the story, illustrated by the well-worn document.

Now let it be said it was Willie himself who pointed out the creative modifications he made to the entries in the report card telling the tale without inhibition. As he put it at an earlier gathering of our tight band, when he had first shown us this memento, "I wasn't the greatest student back then, so I tried to make it look like I'd done better than I had. I did not want my mom and dad mad at me." So, since in those days we were given the report cards to take home for our parents to review, sign, and return same to the teachers, wily Willie changed and/or added some numbers to make some things look better.

Now let it be said it was Willie himself who pointed out the creative modifications he made to the entries in the report card telling the tale without inhibition. As he put it at an earlier gathering of our tight band, when he had first shown us this memento, "I wasn't the greatest student back then, so I tried to make it look like I'd done better than I had. I did not want my mom and dad mad at me." So, since in those days we were given the report cards to take home for our parents to review, sign, and return same to the teachers, wily Willie changed and/or added some numbers to make some things look better.He might have gotten away with it, except when he decided to add some creative comments about his academic prowess. In the block on the lower right side of the document, above Director Aurelio Baldor's stamped purple signature there is a short statement: "Muy buen alumno." Translation: "Very good student." "Problem was," Willie explained, "mom and dad decided the writing looked too much like my handwriting...so I got in trouble anyway!" Nevertheless, thanks to the kind, academic ministrations of Caridad, all was well in the end - Willie and his friends went on to First Grade in September 1956.

Blogger has this to say about his friend Willie...in the School of Life, from what little Quiroga has seen, Wilfredo has passed all arduous tests with flying colors. Our other marvelous mates have done so as well - not to say it has been an easy ride.

Well, let us backtrack a little bit. All good things must come to an end. After our obviously very warm and enjoyable year in Caridad's class, we more or less eagerly trudged into First Grade.

We had a new Profesora, or teacher, Srta. - meaning "Ms." - Elsa Delgado. Funny, we do not seem to remember much about her; this is not to cast aspersions or make anyone think we did not like her. Her face in the yearbook page seems to convey calm and kindness; we certainly have no negative memories of her. Perhaps one's first teacher has a greater impact on memory, for good or bad. For us, the memories of our first teacher are good plus ultra! We do hope and pray life has treated Ms. Delgado well and that, like Caridad Lobato, she had a successful career as a teacher or whatever other profession she chose to pursue. May she also have been blessed to escape the castro-claw...

As we lined up for our yearbook pictures in 1956-1957, so we lined up for a VIP - Very Important Picture - moment with our much-loved Profesora Lobato in 2009.

OK, guess it is not fair to make you work hard at guessing who's who...people change a wee bit in half a century's time; so here is the line up, left to right: Willie, Carlos, Carlos, Albert, and Warren; Caridad in front, as it should be. Ladies first, teachers first.

The unforgettable evening was coming to a close, but Carlos Cueto's camera once again captured another magic moment, recording our teacher's enjoyment over the small tokens of affection we had given her.

She surprised us with a tasty token of affection, lovingly made by her own hands - this luscious - call it a combination flan-and-pudding loaded with fruit - was delicious and quickly disappeared; but its sweet memory is preserved by photography forever! Our Profesora has obvious and considerable talents in the dessert-making arts. But the best evidence of her love and appreciation for us were her words: "If God were to call me Home tomorrow, the memory of this day would live in my last earthly thoughts..."

In Baldor-blogger's personal opinion, the nicest, most poignant token of affection towards our teacher was the poem Willie composed for her. A wonderful poem it is; yet he does not think of himself as being academically gifted...methinks he is too modest. Here are the words of our Preprimario B Bard's poem, dedicated to Caridad Lobato. Fear not, reader - it will be translated for you, to the best of the editor's ability, fearing nevertheless the translation will not do justice to the original.

A LA BELLA PROFESORA CARIDAD LOBATO:

CON EL MISMO NOBRE DE LA VIRGEN

NOS EMPEZO A MOLDEAR

VINO EL MONSTRUO A LA ISLA, MAS BELLA EN ESTE MAR,

ELLA PENSO QUE AL SEPARARNOS SU TRABAJO NO PUDIERA TERMINAR,

38 AÑOS HAN PASADO Y PARECE QUE FUE AYER

Y SEGUIMOS VISUALIZANDO NUESTRO QUERIDISIMO BALDOR

CON SUS EDUCADORES EJEMPLARES E IDOLOS PARA NUESTRAS SIGUIENTES GENERACIONES.

AUN LOS QUE NO SACABAMOS BUENAS NOTAS NOS SEMBRARON LAS SEMILLAS DE RESPETO, ORGULLO, VALOR, Y BONDAD ENTRE MUCHAS OTRAS CUALIDADES,

LE DAMOS GRACIAS A ESA "CAMPESINA" QUE NOS ENAMORO PARA ESTE UNICO GRAN VIAJE DE LA VIDA,

Y COMO VE NOS EVOLUCIONAMOS Y CULTIVAMOS MUY BIEN.

" ENCANTADO DE LA VIDA"

Forgive blogger for doing a bit of editing, adding some punctuation here and there in a desperate attempt to preserve the essence, the "flavor" of the original; a small caveat as well is in order: Where Wilfredo speaks of 38 years going by - regretfully it should be 53...but this all-too human error is understandable; after all, we are desperately seeking to recover a very significant fragment of our past. If only it were 38 years, Willie!

WITH THE SAME NAME AS THE VIRGIN

SHE US BEGAN TO MOLD

CAME THE MONSTER TO THE ISLAND MOST BEAUTIFUL IN THIS SEA

SHE THOUGHT WHEN WE PARTED HER WORK WOULD NOT BE COMPLETE

38 YEARS HAVE GONE BY, YET IT SEEMS IT WAS JUST YESTERDAY

WE CONTINUE VISUALIZING OUR BELOVED BALDOR

WITH ITS EXEMPLARY EDUCATORS, IDOLS FOR GENERATIONS FOLLOWING

EVEN IN THOSE OF US NOT BLESSED WITH GOOD GRADES, THE SEEDS WERE PLANTED WHICH

BLOSSOMED INTO RESPECT, PRIDE, COURAGE, AND KINDNESS, AMONG MANY OTHER QUALITIES

WE GIVE THANKS TO THAT “COUNTRY WOMAN” WHO MADE US FALL IN LOVE, FOR THIS AND ONLY GREAT JOURNEY THROUGH LIFE

AND AS YOU CAN SEE WE EVOLVED AND WERE WELL CULTIVATED

"ENCHANTED WITH LIFE"

Now, you are offered the opportunity to enjoy the live reading - the Baldor Poetry Hour - well, more like a minute and a half or so. Just point your "mouse" arrow to the box with the right-pointing triangle, bottom left, and "click"...the "mouse" that is. It is a "left" click, for you sinister types...

"Enchanted with life" indeed, my Baldor Brother Poet...and with this day of celebration, with our enchanting Profesora, and the enduring, unbreakable friendship of our Preprimario B Band; with our school and all Baldor-eans, past, present...and future; with that beautiful place and time, never to be forgotten. This is dedicated to Caridad Lobato, to you my Brothers and Sisters of Baldor, the Baldor family, and all the great educators there from whom we were privileged to receive instruction. God Bless and keep you!