Return to Wall Street

Hi! Sorry for the failure to keep this Havana log more current. As your blogger said at one point, sometimes things are done as time and the requirements of daily life permit. At least many of us can be thankful we are not robbed of precious time standing in one of those seemingly endless queues Habaneros have endured for over 45 years.

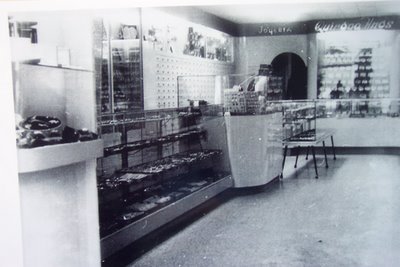

In the last post, I stated my regret at not having any images of Quiroga Hermanos - the interior of the store, that is - to share with you, faithful and patient readers. Well, thanks to cousin Jimmy Quiroga, who continues the tradition and followed the footsteps of his father Manuel into jewelry design and sales, there are after all a couple of period images of Muralla 458 to enjoy.

The photograph dates from about the mid-1940s, before my parents married. It is of the ground floor, where retail customers would examine the fine items for sale, haggle and bargain, bring watches in for repairs, and just plain "window shop" or "counter shop," according to their mood and/or the state of their wallets. If you, or someone in your family, or a friend, ever shopped at Quiroga Hermanos, you would have been served by Dario, or Manuel, or Nicanor ("Nick") or other Quirogas and their capable employees, able and willing to fight hard for your business.

For some reason, however, when I used to visit the store, I seemed to remember the upper floor best. Well, that's because I would usually be taken "up there," to greet my dad, or my uncles and aunts, and other employees who knew the little brat. Here is where watch repairs were done, inventories organized or classified for display and sale, required bookkeeping done - all without the help of computers, cell phones, electric typewriters, hand or electric calculators - remember those? - and the many other electric and electronic aids which make these activities such a breeze today. Well, relatively speaking, that is. On the other hand, the Quiroga brothers did not have to worry about computer crashes, hacking, out of control emails, spamming, identity theft - at least in the digital sense - and so on. Somehow, they ran a successful business without these wonderful, but sometimes chaos-inducing systems. Granted, it took more bodies to accomplish the necessary tasks, but it provided employment for most of the family, and quite a few unrelated folks as well.

Now, if you look at the background, sitting immediately left of the white pole is my father - or at least, very likely to be him. Unfortunately, the available photograph is not the clearest. To his left is his brother Dario - he and his family were the subject of an earlier post; he was the 'cycle fiend in the family, but no "Rebel Without A Cause." To dad's right appears to be his sister, my aunt, Bertha Cortes de Quiroga - I hope some Quirogas will read this and correct me if I am wrong. On the right side of the room, across the "bridge," so to speak, is aunt Cuca, Manuel Quiroga's wife. And to her right is almost certainly my aunt Josephine, who later ably helped mom and dad at Palladium Jewelry. You might remember, and if not, read the earlier posts, that mother and her sisters also worked at Quiroga Hermanos - the venue where my parents were to meet, resulting, among other things, in this blog many years later...!

The two men on the left, obviously employees, are unfortunately unknown - at least to your blog author. Again, some Quiroga might come to the rescue and add another of the missing pieces of information to complete the puzzle.

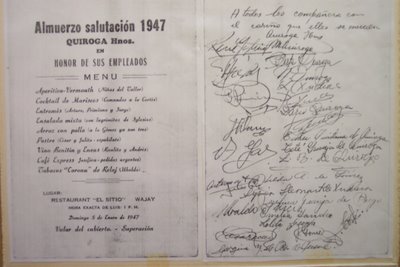

Lest you think it was all work and no play at Quiroga Brothers, the notion will be belied by this image, dating to 1947, of an enjoyable gathering of Quirogas, Granjas, and others at a popular restaurant outside Havana, "El Sitio." The dishes on the menu displayed were named after family members and/or employees. Example: the second item on the menu, from the top, was "Cocktail de Mariscos." Seafood cocktail, that is, and you wonder, what the heck means "Comandos a lo Cortes?" Well, at that time, "comandos," or "commandos" was slang for sun-blocking eyepieces or glasses, these being the same type glasses used by WWII Allied commandos. These came in vogue after the war. "Cortes" refers to Jesse Cortes, who married one of my aunts on father's side, Berta, and whose specialty was eyewear, sold at Quiroga Brothers. Later, as he was an optician, he opened his own shop in Old Havana, and around 1959 I got my first pair of corrective eyewear there, after unsuccessfully trying to hide my increasingly Mr. Magoo-like myopia from Nick and Teresa. Even the menu has its own story to tell, but we have limits both of time and space.

At the center of the table sit my paternal grandparents, Dario Quiroga and Pastora Enriquez de Quiroga. Teresa, my mother, is behind Pastora, and dad stands behind her. Moustachioed uncle Dario stands to father's right - or left, from your point of view, with his wife Loli in front. George the photographer's parents, remember? Look to the right, where the tables join - the man leaning forward sports a set of "commandos." He was Rene Iglesias, one of the salesmen - remembered as a "simpatico" guy. To Iglesias' right is uncle Manuel, or "Manolo," and next to him, his wife Esther, or "Cuca," as we knew her. Directly behind Mr. Iglesias stand aunt Josephine, mom's sister, and her better half, Fernando Prego. He was in the insurance business. In the background, sporting a bow tie and standing next to his wife, my father's sister Berta, is Jesse Cortes. "Commando" Cortes, as in the menu - but not wearing "commandos," interestingly. There are other family members, employees, and friends to meet, but you are by now am sure weary of all the social introductions, so we shall go on with the rest of the story.

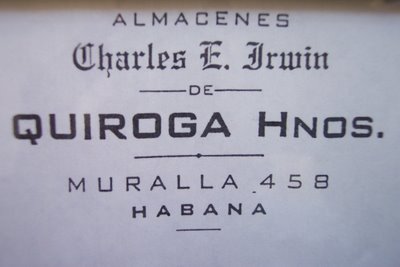

Dad went to work as a 14-year old, for what would become Quiroga Hermanos, in February 1934. At the time, the business was owned by an American, Charles Irwin. The last time your writer discussed this, he made an error and accidentaly referred to Mr. Irwin as "Charles Irving." But, in fact, it was Mr. Irwin who owned and ran the business, with my father's brothers and other employees. This error came to light not only in talking about it with father, but also when he showed me one of the surviving business cards from the time right after the Quirogas purchased the business. And, to use an old saying, "the proof is in the pudding," as you can see.

This past weekend I was fortunate to have some quality visiting time with mom and dad. Being in the midst of this post, and curiosity having been aroused about things related to Quiroga Brothers and Charles Irwin, asked them to bear with me and allow me to pester them with pertinent questions on the current subject - to which they graciously consented. Hey, after all, I am NOT a NY Times reporter, and hopefully can be trusted - at least a little...

Hereby is the narrative, from the interview with Mr. and Mrs. Quiroga - who maybe should take over this blog and tell the story directly and unfiltered. They could certainly do a more adequate and eloquent job than this wannabe reporter.

We'll start with the VIP in the story, as he is the one who started the business. Charles Eugene Irwin was from Akron, Ohio. At first, dad thought he was from Toledo - not Spain! - Toledo, Ohio. But curiosity getting the better of the blogger, decided to "google" (you know what that means, right?) Mr. Irwin and see what might turn up. Well, not much. However, an interesting morsel was found via rootsweb.com,involving World War I civilian draft records for Monroe County, Florida. Monroe County comprises the Florida Keys, and as there was physical and cultural closeness between Key West and Havana in those days, no doubt Mr. Irwin would have immigrated to Cuba via the Florida Keys and left his imprint, albeit small, in Monroe County. These records listed a Charles Eugene Irwin, born September 9, 1876 in Akron, Ohio. There was an interesting note appended to the record: "Lives in Havana,Cuba." Undoubtedly, this is "our" Charles Eugene Irwin, given the details father was able to provide about him. One wonders if he made his way to Cuba as a result of Army or Navy service during the Spanish-American war, but since father does not recall any talk about that from Mr. Irwin, this is just speculation. It would be interesting to learn what brought him from so far to settle in Havana. That certainly could provide fodder for another blog. Maybe one of our Buckeye State readers - if we have any - would kindly enlighten us. By the way, the Toledo connection may have to do with, according to father, as told by his brother Dario, Mr. Irwin having supposedly played ball there with an "AA" league team.

Dad explained that his brother, my uncle Dario, who knew Mr. Irwin first, had told dad "Mr. Charles," as he was known to many of the vendors and customers who stopped by his store, had opened a store in 1907 at Compostela Street in Havana. At the first location, on Compostela, he sold jewelry and other retail goods. Years later, he relocated to Muralla Street, number 458. The store was named, simply, "Charles E. Irwin Company." Uncle Dario started working there in 1930, and dad became an employee in February 1934 - "my brother Dario put in a good word for me and Mr. Irwin hired me." "Mr. Charles" wound up hiring quite a few members of the Quiroga and Granja (mom's side) families to run the operation, and evidently was pleased with them - never did I hear of any being let go. My aunt Josephine joined the happy group in 1935, and mother in 1942; by the time she came on board, however, Mr. Irwin, unfortunately, had passed away and the business had become Quiroga Brothers - aunts and uncles galore earned their daily bread there, as well as parents-to-be.

Dad went on to say that during the years he ran the business, Mr. Irwin lived above the store, something quite common in Havana in those days, and even today in many cities and towns in Europe and other parts of the world. No commuting worries there. The building had 3 stories, of which 2 were dedicated to the business, and the 3rd for living quarters, several apartments having been built there.

Although not married, he had a companion, who was also involved in managing the company - she was, excuse me ladies, his "right hand man," not a bad way to describe her, as from what father and mother told me, she was kind of blunt and tough, although not unpleasant - unless you rubbed her the wrong way. She was an Italian immigrant, one of many who had come to Cuba. She was Elisa Cremonesi Triulzi and hailed from Cremona - hence the surname. Father smiled, obviously recalling her personality, as he told how "she claimed to be of aristrocratic background, and had a tendency (we would call it "political incorrectness" today) to speak deprecatingly about southern Italians, calling them 'Paduanos' ("Paduans," in reference to the town of Padua - or, I suppose, "Padovanos" in Italian) which back then was a euphemism for peasant or low-class person." Evidently, Ms. Cremonesi had no qualms about, no political incorrectness intended, "calling a spade a spade." She was, in fact, the person who nicknamed dad "Nick" or "Nicky," no pun intended folks, really. "Nicanor - that is too long and complicated! You'll be 'Nicky' from now on." So dad became "Nick" or "Nicky" to family, friends, and acquaintances. Mother said this caused some confusion. "Some people thought 'Nick' was short for 'Nicolas' and we had to set them straight." So one form of confusion led to another, thanks to Elisa Cremonesi Triulzi.

Father learned some colorful Italian words and phrases from her, gems such as "lavare la testa al asino e perdere tempo e sabone" - "to scrub the head of the donkey is to waste both time and soap." Which no doubt Ms. Elisa used in the presence of obtuse or dense folks, sotto voce. Or possibly she meant this as a comment on the hygiene of the less intellectually fortunate. Who knows? Another: "Suspira Cesare miserere per la sua Cleopatra" - "Sighs Caesar in misery for his beloved Cleopatra."

The eloquent Elisa passed away in Havana, around 1943, having sold Charles E. Irwin and Company to the brothers Quiroga April 19, 1941.

And what was it like to work for Mr. Irwin? Well, not a negative word from mother or father about him. "He was a good boss, a nice boss," father said. "Nick" started out as a messenger boy, doing deliveries and picking up merchandise, going to the Post office, and to Customs - located at the end of Teniente Rey and Oficio streets - to pay required import duties levied on foreign goods. "Mr. Irwin bought jewelry from Czechoslovakia, among other places," father explained. He was also tasked with cleaning and dusting display counters, which he did several times a day. "It was dusty in those pre-air conditioning times and the dust quickly layered those counters," he recalled.

He continued, pulling these great recollections from his incredible memory bank. "Charles Irwin was even-tempered, but firm when necessary. He spoke perfect Spanish, but with a Mid-Western American accent. He often used the expression 'pero hombre...' to preface his comments, whenever he wanted to drive home a point. He was given to making colorful, pointed statements - if you were to say to him, 'Mr. Irwin, I believe...,' he would interrupt you politely and interject 'Pero hombre...no hay que creer; hay que saber' - that is, 'But man...no need to believe; one needs to know.' He wanted you to have your facts straight before you commited to making statements or taking actions." Obviously, Mr. Irwin would not have cut it as a New York Times reporter, which speaks well for him.

Continues "Nick:" "He liked to go to a corner bar/eatery, 'El Escorial,' where he would order bananas and milk for breakfast, to the horror of the help who, as did many Habaneros then, thought the combination poisonous because it was believed this would turn the inside of your stomach black and do you in." Why it did not occur to these folks the premise had to be false, after seeing Mr. Irwin return day after day to consume his "poison," is beyond me. Each culture has its share of pseudo-scientific myths, this being one of them; which recalls the set-in-stone belief in vogue during my Havana days, that one was not to swim unless one had given his tummy a full THREE hours to digest a meal, no matter how small...which in my case, led to battles with my mother, a tug of war between eating and swimming, in which circular arguments from both sides clashed in a knightly joust. "I wanna go in the water!" "Well, you gotta have some lunch first!" "No! Because then you won't let me go in the water!" "Well! You can't go in the water before you have lunch!" I bet Mr. Irwin woulda had lunch AND gone in the water...

Dad continued with his recollections and anecdotes. At the time, Mr. Irwin would close for lunch from noon to 2:00 PM. This nice break would afford father enough time to walk home, home being Aguila Street number 71-A "later changed due to new or reassigned street numbers to Aguila 257," across from the "El Mundo" newspaper offices. "Mr. Charles" usually asked dad to stop on the way home, at Puerta Del Sol restaurant, Egido and Bernaza Streets, and ask them to prepare something for Mr. Irwin's own lunch. Call-in service sans telephone, when you think about it. One day he asked dad to tell Mr. Machado, the manager of Puerta Del Sol, to "fix some baked potatoes." "Nick" went merrily on his way to his anticipated lunch at home, forgetting both message and mission.

After returning, no doubt satiated and satisfied, from his lunch break, he was embarrassed when, very calmly, Mr. Irwin asked "if he had forgotten something." "Oh, I am sorry! I forgot to order your lunch!" To which Mr. Irwin retorted in his Midwestern Americano-Cuban accent: "Pero hombre! Olvidando no se va hacer rico." "But man! You won't get rich by forgetting." Rich advice, indeed.

Sadly, "Mr. Charles" was stricken by a cancer - "cancer of the bronchi, I believe," said father. In those pre-war (meaning pre World War II) days, treatment options were very limited. "He was treated with radium, applied to his chest, which burned him so his chest was red and raw," explained father. It cannot have been pleasant. We were reminded that radium had been discovered by the Curies, Pierre and Maria, and later blamed for Maria Curie's premature death. So, it seems the remedy for dad's unfortunate boss was almost worse than the cure - if not the cancer, the radiation would in time have poisoned him. Mr. Irwin passed away in 1939, followed by Elisa, his "right-hand woman," in 1943. Sad as this may have been, they were at least both spared seeing their beloved Havana stricken by a metastatic, political cancer 20 years later...for which we still await a cure.

How many of you know who Shirley Temple is? Maybe you recognize her better as Shirley Temple Black? Well, if you know who she is you are at least as old as I am. She was a popular child star in the 30s and 40s. So, you ask, what's the connection and what's the point? Well, one item sold at Charles E. Irwin & Co. was the then-popular Shirley Temple doll. And mother was a big Shirley Temple fan. One day, to her delight, she became the joyful recipient of a Shirley Temple doll, courtesy her sister Josephine; "a complete surprise," mom commented, "and I was delighted." That was just like aunt Josephine - always sweet and thoughtful.

(from www.classicmoviekids.com)

(from www.classicmoviekids.com)This nice file photo of Ms. Temple in Scottish Highlander dress uniform leads me to a brief flight of fantasy...where I picture her drawing a bead on a certain abominable, bearded 'n stinkin' creature...Bang! "Ye got 'im, miss! Excellent shooting!" Please, allow me my fantasies - isn't that what classic movies are all about?

And this is what mother's doll looked like. Unfortunately, she no longer has it, so this image from www.scoop.diamondgalleries.com will have to do.

And this is what mother's doll looked like. Unfortunately, she no longer has it, so this image from www.scoop.diamondgalleries.com will have to do.Thinking of Muralla street reminded me of a blog named Wall Street Cafe, authored by a lady whose blog name is "La Ventanita," or the "Little Window." The blog is so named because, as stated therein, "The page's name honors my father's private business in Cuba - Wall Street - a restaurant bar in La Habana B.C." So this blogger asked his father if perhaps the Havana Wall Street Cafe had been named because of its proximity to Muralla - which means Wall - street. "No," he answered. "Wall Street Cafe was located around Obrapia and Aguiar streets. It was likely named that because it was in an area where you found banks, stock brokers, insurance companies,and other financial institutions, including the Havana Stock Exchange." Yes, Havana had a stock exchange of its own.

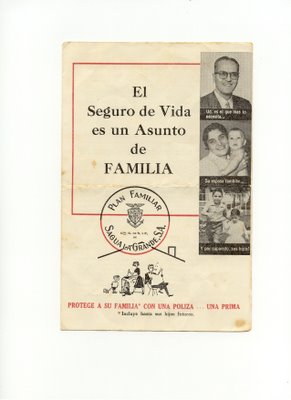

Aunt Josephine's husband - or husband to be, my uncle Prego - worked in an insurance firm in that area, "Cia (Spanish abbreviation for company) General de Seguros y Fianzas de Sagua La Grande, S.A." "S.A." corresponding to "Inc." as in "incorporated." He was employed as a salesman and adjuster/investigator for worker's compensation cases.

The company's exact location was Cuba and Obrapia streets. Interestingly, there is a direct connection between this insurer and your blogger - our family association with uncle Prego later led to my older sister Martha's - and my - only foray into the field of advertising and promotion, as you will see in this informative little pamphlet we were fortunate enough to save from the dustbin of time:

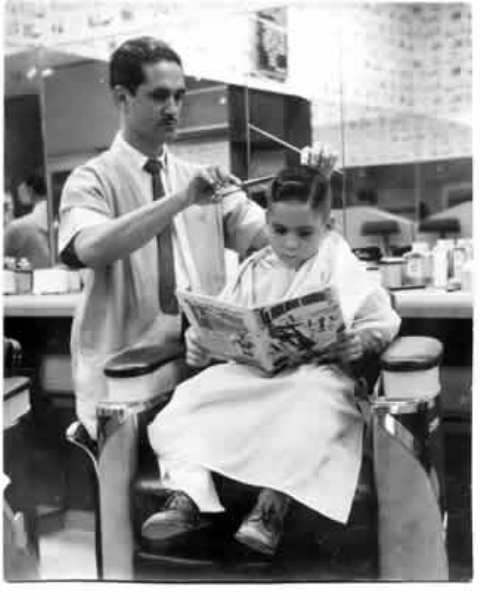

Surely you can find us, no? This dates from around 1959. The photo setting was actually the gardens and pool area of the Focsa building, where we lived at the time.

Uncle Prego asked mom and dad if we would participate in the publicity shoot, and there you are! No, we did not get paid for this - it was a "family favor" if you will. We had a good time doing the "shoot." And you don't turn down your good uncle when he needs you. No movie or advertising contracts resulted from this, however. Which is just as well, as not long after that, the insurance and advertising industries would disappear from Cuba.

Ah, in case you are wondering what kind of insurance policy or contract you could buy from Sagua La Grrande, S.A in those days, here is the rest of the pamphlet. Apologize for not translating it, but you'll get the picture.

The Beguiristain family from the town of Sagua La Grande owned this company, hence the name. As happened to many others, they lost control when the "revolutionary government" carried out a program of sweeping confiscations of industrial, banking, and insurance enterprises in October 1960, following the passage of the infamous "laws" justifying this theft, Decrees 890 and 891 of October 13, 1960.

Back to more pleasant subjects, as we make our way through this part of Old Havana. Mother and father fondly recalled a combination bakery/delicatessen/grocery or "bodega" named "La Caoba," found between Habana and Aguiar streets. "You could get all kinds of breads, pastries, and products from Spain, such as hams, sausages, and such. It was very popular with both blue-and-white collar workers," explained father. Mom added: "Around 10:00 A.M. it would get busy, lots of people walking in to get coffee on their breaks." The smell of brewing cafe Cubano must have been a wonderful tonic to these workers. Makes me want some now - but better hold off, getting late, and gotta get some sleep...kinda hard with a Cuban caffeine jolt.

"We also liked another eatery, specializing in Spanish cuisine, not far from 'La Caoba.' This was 'El Baturro,' on Egido street; the owners were the Romualdo Lalueza family from Aragon, Spain." As I listened intently, my stomach started growling, from the thought of all the good eating that undoubtedly went on in these places. Not a bad place to work in, Old Havana, with all these choices. Little choice now, for an Habanero. Now, only foreign tourists have choices. Havana is today the fiefdom of a cruel and selfish glutton.

And where did the ladies and gentlemen laboring at Sagua La Grande S.A. insurance like to hang out on breaks and lunch? At "El Botecito" cafe on Aguiar street - just a short walk from the company offices. Another gem from my dear parents' memory chest, and then we'll end this tour: "There was yet another place where you could get nice pastries, not far from Muralla 458. This was at 'Cafe Europa,' Aguiar and O'Reilly streets, where every weekday, around 10:00 A.M. trays of pastries stuffed with meat or fish ("pastelitos," to the Cubans) were brought out. The server behind the counter would ask the prospective customer, 'tiburon o perro (shark or dog)?,' meaning 'do you want a meat or fish pastry?'" Pretty innovative way of getting the customer's attention, and illustrative of Cubans' irrepressible sense of humor, then and now. And now, more than ever, it takes much sense of humor to make it through a typical day in crumbling Havana. Someday, not too far down the road, I have faith that, once again, in a revived and restored city, somewhere around Aguiar and O'Reilly, some jocular server behind the pastry counter will again cry out, "tiburon o perro?"

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home